The Struggle is Real: Why Productive Struggle Really Matters!

- Heather Cameron

- Jul 29, 2022

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 8, 2022

Let's take a moment and think about how a baby learns to crawl. For months caregivers will use tummy time to help build core muscles that the baby will use to begin to sit, crawl, and eventually stand. It's not an instantaneous process, and babies (at least all of mine) haven't really enjoyed tummy time. Why? Because it's hard, but it's so very important for their development. By providing this productive struggle parents are giving their babies the skills and exercise they need to learn to crawl. A similar situation is when babies learn to walk. Parents are motivators and ensure their safety, but it is up to the child to take a few steps, fall, and get back up again. This is another example of productive struggle. The opportunity to practice something that is difficult to learn something new. There are so many examples of these types of life-lessons; riding a bike; learning how to follow directions; becoming good at sports or musical instruments etc. Think about a time in your life where you learned an important lesson. Why does this event stick out for you? Maybe you learned from a mistake, or had to grapple with a few different solutions to come up with the right answer. Some of the biggest lessons we learn in life come from situations where productive struggle was necessary.

Productive struggle in maths is important for student understanding and retention of math topics and ideas. Dewey (1929), recognized the contribution of effort in developing new ideas. Valentine & Bolyard (2018, p. 4) stated that, "providing opportunities for students to struggle with important mathematics plays a key role in learning that results in conceptual understanding." Conceptual understanding means that one knows more than isolated facts and can apply their understanding to appropriate contexts. Many of us [myself included] did not experience productive struggle in our math classrooms, and now we often default to being helpers. There is dissonance for us, and as parents and educators we want to prevent and avoid struggle for our students/children. There is a time and place to be the helpers, but when it comes to learning math we need to be the facilitators guiding the learning.

How can we encourage productive struggle by being strategic with the questions we ask kids to answer?

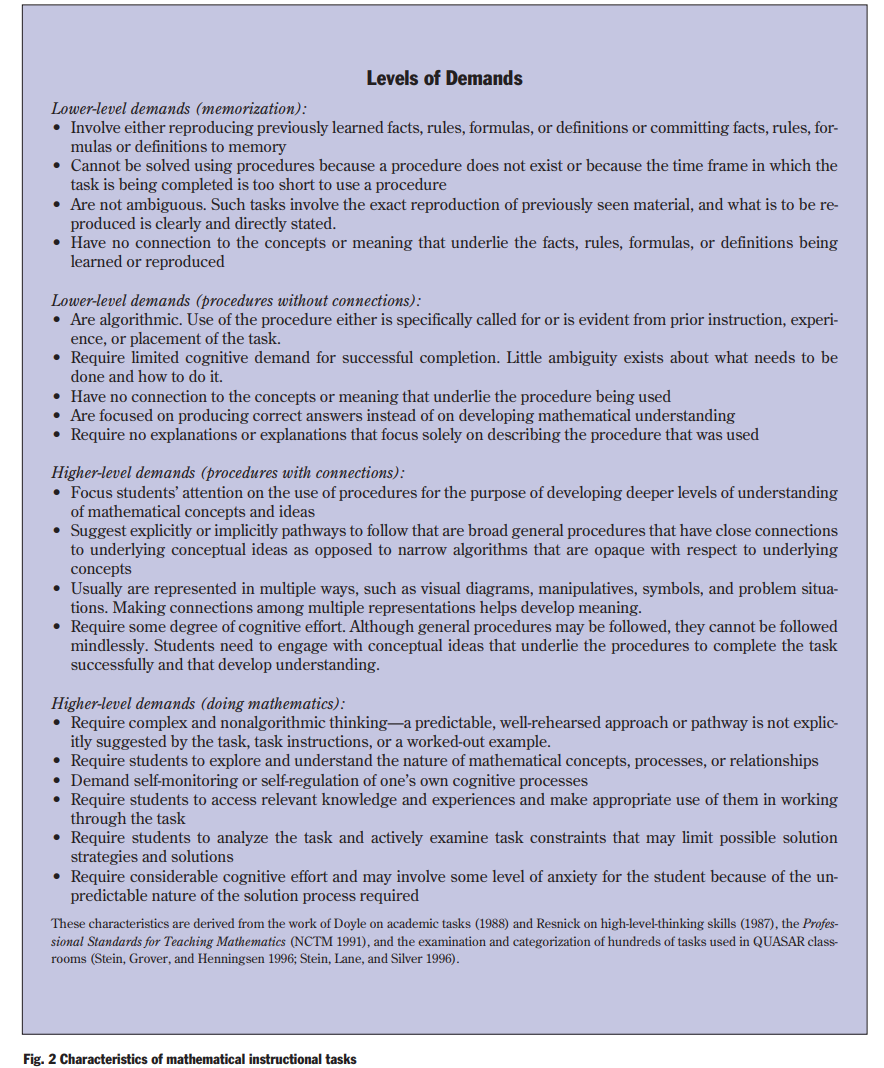

Smith & Stein's Levels of Demands chart [which you may recognize from the What's Math Got to Do With It post] describes different kids of math instructions seen in classrooms. Their research found that "the highest learning gains ... were related to the ways that engaged students in high levels of cognitive thinking and reasoning" (Smith & Stein, 1998, 344). If you look at the qualifications for "doing mathematics" they are tasks that require some type of productive struggle. The key for educators is to find the balance. Tasks that are far too easy will find students bored and disengaged, and tasks that are too difficult will find students anxious and frustrated.

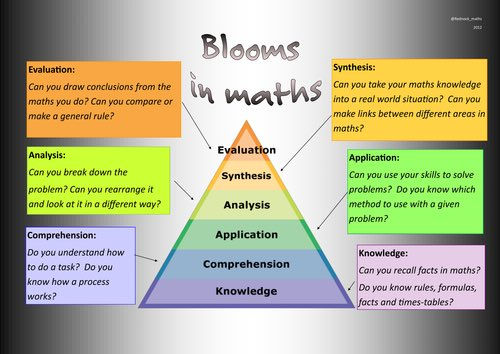

Iain McDermott shared this graphic on his twitter page, and there are similar parallels between Blooms Taxonomy and Smith & Stein's research when it comes to providing students with tasks that move beyond a surface level of understanding. These higher level thinking tasks require productive struggle. They require critical thinking, analyzing, and evaluating their current knowledge of math in order to make important learning connections.

This is all great in theory, but I know you are wondering what this actually looks like. The reason you'll hear me give text books a hard time is because they often take the thinking out of the task [Check out Dan Meyer's Math Class Needs a Makeover Ted Talk -- I've linked this in the Inspirational Videos section]. Text books are often too helpful, but we can use some of the questions and manipulate them a little by just giving students less information to work with. "What real world math gives you all of the given variables?" (Meyer, 2010).

So, incorporating productive struggle may be easier than you think. At home find ways to apply what your child is learning in school to math around the house or in the community. For example, kindergarten and primary age students can identify shapes they see when out for a walk, count dishes when emptying the dishwasher or count their toys when putting them into their buckets after playing with them. Junior and intermediate students can help estimate the cost of groceries, and help with measurement and financial planning of renovation projects. Math can be found everywhere and having your child apply what they are learning in school to activities you do as a family will help to make those important connections. When doing math together remember to let them struggle through the problem. Encourage them, lead them, and let them grapple with the problem. They will love the opportunity to spend quality time together. You'll be creating memories and providing them with important life skills - win-win!

References:

Dewey, J. (1929). The quest for certainty. New York, NY: Vintage Books

Smith, M., & Stein, M. (1998). Selecting and creating mathematical tasks: From research to practice. Mathematics Teaching in the Middle School 3 p. 344-350.

McDermott, I. (@iain_mcd). (2016). Skilled questioning unlocks understanding. Twitter. https://twitter.com/iain_mcd/status/774517792322166784

Meyer, D. (2010). Math class needs a makeover.....

Valentine, K., & Bolyard, J. (2018). Creating a classroom culture that supports productive struggle: Pre-service teachers' reflections on teaching mathematics. American Educational Research Association: New York.

Comments